CheapASPNETHostingReview.com | Best and cheap ASP.NET hosting. “Creating a mathematical expression evaluator is one of the most interesting exercises in computer science, whatever the language used. This is the first step towards really understanding what sort of magic is hidden behind compilers and interpreters….“.

I agree completely, and hope that you do too.

Using the CalcEngine class

The CalcEngine class performs two main tasks:

- Parses strings that contain formulas into

Expressionobjects that can be evaluated. - Evaluates

Expressionobjects and returns the value they represent.

To evaluate a string that represents a formula, you call the CalcEngine.Parse method to get an Expression, then call the Expression.Evaluate method to get the value. For example:

1 2 3 | var ce = new CalcEngine(); var x = ce.Parse("1+1"); var value = (double)x.Evaluate(); |

CalcEngine.Evaluate method directly. This parses the string into an expression, evaluates the expression, and returns the result. For example:1 2 | var ce = new CalcEngine(); var value = (double)ce.Evaluate("1+1"); |

The advantage of the first method is that it allows you to store the parsed expressions and re-evaluate them without re-parsing the same string several times. However, the second method is more convenient, and because the CalcEngine has a built-in expression cache, the parsing overhead is very small.

Functions

The CalcEngine class implements 69 functions, selected from Excel’s over 300. More functions can be added easily using the RegisterFunction method.

RegisterFunction takes a function name, the number of parameters (minimum and maximum), and a delegate that is responsible for evaluating the function. For example, the “atan” function is implemented as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | var ce = new CalcEngine(); ce.RegisterFunction("ATAN2", 2, Atan2); static object Atan2(List<Expression> p) { return Math.Atan2((double)p[0], (double)p[1]); } |

Function names are case-insensitive (as in Excel), and the parameters are themselves expressions. This allows the engine to calculate expressions such as “=ATAN(2+2, 4+4*SIN(4))”.

The CalcEngine class also provides a Functions property that returns a dictionary containing all the functions currently defined. This can be useful if you ever need to enumerate remove functions from the engine.

Notice how the method implementation listed above casts the expression parameters to the expected type (double). This works because the Expression class implements implicit converters to several types (string, double, bool, and DateTime). I find that the implicit converters allow me to write code that is concise and clear.

If you don’t like implicit converters, the alternative would be to override ToString in the Expression class and add ToDouble, ToDateTime, ToBoolean, etc.

Variables: Binding to simple values

Most calculation engines provide a way for you to define variables which can be used in expressions. The CalcEngine class implements a Variables dictionary that associates keys (variable names) and values (variable contents).

For example, the code below defines a variable named angle and calculates a short sine table:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | // create the CalcEngine var ce = new CalcEngine.CalcEngine(); // calculate sin from 0 to 90 degrees for (int angle = 0; angle <= 90; angle += 30) { // update value of "angle" variable ce.Variables["angle"] = angle; // calculate sine var sin = ce.Evaluate("sin(angle * pi() / 180)"); // write it out Console.WriteLine("sin({0}) = {1}", angle, sin); } // output: sin(0) = 0 sin(30) = 0.5 sin(60) = 0.866025403784439 sin(90) = 1 |

Variables: Binding to CLR objects

In addition to simple values, the CalcEngine class implements a DataContext property that allows callers to connect a regular .NET object to the engine’s evaluation context. The engine uses Reflection to access the properties of the object so they can be used in expressions.

This approach is similar to the binding mechanism used in WPF and Silverlight, and is substantially more powerful than the simple value approach described in the previous section. However, it is also slower than using simple values as variables.

For example, if you wanted to perform calculations on an object of type Customer, you could do it like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | // Customer class used as a DataContext public class Customer { public string Name { get; set; } public double Salary { get; set; } public List |

CalcEngine supports binding to sub-properties and collections. The object assigned to the DataContext property can represent complex business objects and entire data models.

This approach makes it easier to integrate the calculation engine into the application, because the variables it uses are just plain old CLR objects. You don’t have to learn anything new in order to apply validation, notifications, serialization, etc.

Variables: Binding to dynamic objects

The original usage scenario for the calculation engine was an Excel-like application, so it had to be able to support cell range objects such as “A1” or “A1:B10”. This requires a different approach, since the cell ranges have to be parsed dynamically (it would not be practical to define a DataContext object with properties A1, A2, A3, etc).

To support this scenario, the CalcEngine implements a virtual method called GetExternalObject. Derived classes can override this method to parse identifiers and dynamically build objects that can be evaluated.

If the object returned implements the CalcEngine.IValueObject interface, the engine evaluates it by calling the IValueObject.GetValue method. Otherwise, the object itself is used as the value.

If the object returned implements the IEnumerable interface, then functions that take multiple values (such as Sum, Count, or Average) use the IEnumerable implementation to get all the values represented by the object.

For example, the sample application included with this article defines a DataGridCalcEngine class that derives from CalcEngine and overrides GetExternalObject to support Excel-style ranges. This is described in detail in a later section (“Adding Formula Support to the DataGridView Control”).

Optimizations

I mentioned earlier that the CalcEngine class performs two main functions: parsing and evaluating.

If you look at the CalcEngine code, you will notice that the parsing methods are written for speed, sometimes even at the expense of clarity. The GetToken method is especially critical, and has been through several rounds of profiling and tweaking.

For example, GetToken detects characters and digits using logical statements instead of the convenient char.IsAlpha or char.IsDigit methods. This does make a difference that shows up clearly in the benchmarks.

In addition to this, CalcEngine implements two other optimization techniques:

Expression caching

The parsing process typically consumes more time than the actual evaluation, so it makes sense to keep track of parsed expressions and avoid parsing them again, especially if the same expressions are likely to be used over and over again (as in spreadsheet cells or report fields, for example).

The CalcEngine class implements an expression cache that handles this automatically. The CalcEngine.Evaluate method looks up the expression in the cache before trying to parse it. The cache is based on WeakReference objects, so unused expressions eventually get removed from the cache by the .NET garbage collector. (This technique is also used in the NCalc library.)

Expression caching can be turned off by setting the CalcEngine.CacheExpressions property to false.

Expression optimization

After a string has been parsed, the resulting expression can sometimes be optimized by replacing parts of the expression that refer only to constant values. For example, consider the expression:

1 | { 4 * (4 * ATAN(1/5.0) - ATAN(1/239.0)) + A + B } |

This expression contains several constants and functions of constants. It can be simplified to:

1 | { 3.141592654 + A + B } |

This second expression is equivalent to the first, but can be evaluated much faster.

Expression simplification was surprisingly easy to implement. It consists of a virtual Expression.Optimize method that is called immediately after an expression is parsed.

The base Expression class provides an Optimize method that does nothing:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | class BinaryExpression : Expression { public virtual Expression Optimize() { return this; } ... |

This simply allows all derived classes that derive from Expression to implement their own optimization strategy.

For example, the BinaryExpression class implements the Optimize method as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | class BinaryExpression : Expression { public override Expression Optimize() { _lft = _lft.Optimize(); _rgt = _rgt.Optimize(); return _lft._token.Type == TKTYPE.LITERAL && _rgt._token.Type == TKTYPE.LITERAL ? new Expression(this.Evaluate()) : this; } .. |

The method calls the Optimize method on each of the two operand expressions. If the resulting optimized expressions are both literal values, then the method calculates the result (which is a constant) and returns a literal expression that represents the result.

To illustrate further, function call expressions are optimized as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | class FunctionExpression : Expression { public override Expression Optimize() { bool allLits = true; if (_parms != null) { for (int i = 0; i < _parms.Count; i++) { var p = _parms[i].Optimize(); _parms[i] = p; if (p._token.Type != TKTYPE.LITERAL) { allLits = false; } } } return allLits ? new Expression(this.Evaluate()) : this; } ... |

First, all parameters are optimized. Next, if all optimized parameters are literals, the function call itself is replaced with a literal expression that represents the result.

Expression optimization reduces evaluation time at the expense of a slight increase in parse time. It can be turned off by setting the CalcEngine.OptimizeExpressions property to false.

Globalization

The CalcEngine class has a CultureInfo property that allows you to define how the engine should parse numbers and dates in expressions.

By default, the CalcEngine.CultureInfo property is set to CultureInfo.CurrentCulture, which causes it to use the settings selected by the user for parsing numbers and dates. In English systems, numbers and dates look like “123.456” and “12/31/2011”. In German or Spanish systems, numbers and dates look like “123,456” and “31/12/2011”. This is the behavior used by Microsoft Excel.

If you prefer to use expressions that look the same on all systems, you can set the CalcEngine.CultureInfo property to CultureInfo.InvariantCulture for example, or to whatever your favorite culture happens to be.

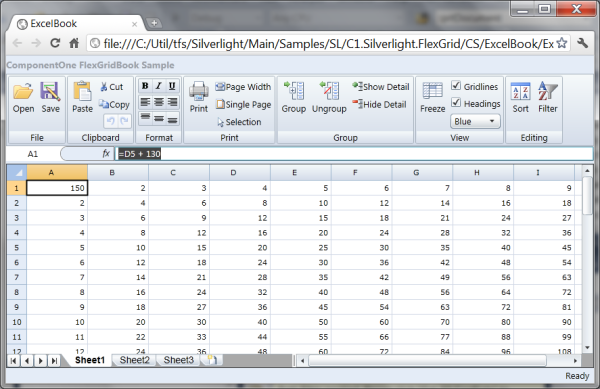

Sample: A DataGridView control with formula support

The sample included with this article shows how the CalcEngine class can be used to extend the standard Microsoft DataGridView control to support Excel-style formulas. The image at the start of the article shows the sample in action.

Note that the formula support described here is restricted to typing formulas into cells and evaluating them. The sample does not implement Excel’s more advanced features like automatic reference adjustment for clipboard operations, selection-style formula editing, reference coloring, and so on.

The DataGridCalcEngine class

The sample defines a DataGridCalcEngine class that extends CalcEngine with a reference to the grid that owns the engine. The grid is responsible for storing the cell values which are used in the calculations.

The DataGridCalcEngine class adds cell range support by overriding the CalcEngine.GetExternalObject method as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 | /// &lt;summary> /// Parses references to cell ranges. /// &lt;/summary> /// &lt;param name="identifier">String representing a cell range /// (e.g. "A1" or "A1:B12".&lt;/param> /// &lt;returns>A &lt;see cref="CellRange"/> object that represents /// the given range.&lt;/returns> public override object GetExternalObject(string identifier) { // check that we have a grid if (_grid != null) { var cells = identifier.Split(':'); if (cells.Length > 0 && cells.Length &lt; 3) { var rng = GetRange(cells[0]); if (cells.Length > 1) { rng = MergeRanges(rng, GetRange(cells[1])); } if (rng.IsValid) { return new CellRangeReference(_grid, rng); } } } // this doesn't look like a range return null; } |

The method analyzes the identifier passed in as a parameter. If the identifier can be parsed as a cell reference (e.g., “A1” or “AZ123:XC23”), then the method builds and returns a CellRangeReference object. If the identifier cannot be parsed as an expression, the method returns null.

The CellRangeReference class is implemented as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 | class CellRangeReference : CalcEngine.IValueObject, // to get the cell value IEnumerable // to enumerate cells in the range { // ** fields DataGridCalc _grid; CellRange _rng; bool _evaluating; // ** ctor public CellRangeReference(DataGridCalc grid, CellRange rng) { _grid = grid; _rng = rng; } // ** IValueObject public object GetValue() { // get simple value (e.g. "A1") return GetValue(_rng); } // ** IEnumerable public IEnumerator GetEnumerator() { // get multiple values (e.g. "A1:B10") for (int r = _rng.TopRow; r &lt;= _rng.BottomRow; r++) { for (int c = _rng.LeftCol; c &lt;= _rng.RightCol; c++) { var rng = new CellRange(r, c); yield return GetValue(rng); } } } // ** implementation object GetValue(CellRange rng) { if (_evaluating) { throw new Exception("Circular reference"); } try { _evaluating = true; return _grid.Evaluate(rng.r1, rng.c1); } finally { _evaluating = false; } } } |

The CellRangeReference class implements the IValueObject interface to return the value in the first cell in the range. It does this by calling the owner grid’s Evaluate method.

The CellRangeReference also implements the IEnumerable interface to return the value of all cells in the range. This allows the calculation engine to evaluate expressions such as “Sum(A1:B10)”.

Notice that the GetValue method listed above uses an _evaluating flag to keep track of ranges that are currently being evaluated. This allows the class to detect circular references, where cells contain formulas that reference the cell itself or other cells that depend on the original cell.

The DataGridCalc class

The sample also implements a DataGridCalc class that derives from DataGridView and adds a DataGridCalcEngine member.

To display formula results, the DataGridCalc class overrides the OnCellFormatting method as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | // evaluate expressions when showing cells protected override void OnCellFormatting(DataGridViewCellFormattingEventArgs e) { // get the cell var cell = this.Rows[e.RowIndex].Cells[e.ColumnIndex]; // if not in edit mode, calculate value if (cell != null && !cell.IsInEditMode) { var val = e.Value as string; if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(val) && val[0] == '=') { try { e.Value = _ce.Evaluate(val); } catch (Exception x) { e.Value = "** ERR: " + x.Message; } } } // fire event as usual base.OnCellFormatting(e); } |

The method starts by retrieving the value stored in the cell. If the cell is not in edit mode, and the value is a string that starts with an equals sign, the method uses CalcEngine to evaluate the formula and assigns the result to the cell.

If the cell is in edit mode, then the editor displays the formula rather than the value. This allows users to edit the formulas by typing into in the cells, just like they do in Excel.

If the expression evaluation causes any errors, the error message is displayed in the cell.

At this point, the grid will evaluate expressions and show their results. But it does not track dependencies, so if you type a new value into cell “A1” for example, any formulas that use the value in “A1” will not be updated.

To address this, the DataGridCalc class overrides the OnCellEditEnded method to invalidate the control. This causes all visible cells to be repainted and automatically recalculated after any edits.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | // invalidate cells with formulas after editing protected override void OnCellEndEdit(DataGridViewCellEventArgs e) { this.Invalidate(); base.OnCellEndEdit(e); } |

Let’s not forget that implementation of the Evaluate method used by the CellRangeReference class listed earlier. The method starts by retrieving the cell content. If the content is a string that starts with an equals sign, the method evaluates it and returns the result; otherwise it returns the content itself:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | // gets the value in a cell public object Evaluate(int rowIndex, int colIndex) { // get the value var val = this.Rows[rowIndex].Cells[colIndex].Value; var text = val as string; return !string.IsNullOrEmpty(text) && text[0] == '=' ? _ce.Evaluate(text) : val; } |

That is all there is to the DataGridCalc class. Notice that calculated values are never stored anywhere . All formulas are parsed and evaluated on demand.

The sample application creates a DataTable with 50 columns and 50 rows, and binds that table to the grid. The table stores the values and formulas typed by users.

The sample also implements an Excel-style formula bar across the top of the form that shows the current cell address, content, and has a context menu that shows the functions available and their parameters.

Finally, the sample has a status bar along the bottom that shows summary statistics for the current selection (Sum, Count, and Average, as in Excel 2010). The summary statistics are calculated using the grid’s CalcEngine as well.

Testing

I built some testing methods right into the CalcEngine class. In debug builds, these are called by the class constructor:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | public CalcEngine() { _tkTbl = GetSymbolTable(); _fnTbl = GetFunctionTable(); _cache = new ExpressionCache(this); _optimize = true; #if DEBUG this.Test(); #endif } |

This ensures that tests are performed whenever the class is used (in debug mode), and that derived classes do not break any core functionality when they override the base class methods.

The Test method is implemented in a Tester.cs file that extends the CalcEngine using partial classes. All test methods are enclosed in an #if DEBUG/#endif block, so they are not included in release builds.

This mechanism worked well during development. It helped detect many subtle bugs that might have gone unnoticed if I had forgotten to run my unit tests when working on separate projects.

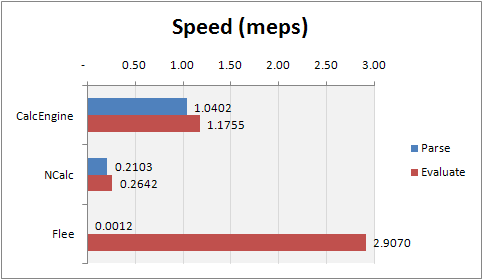

Benchmarks

While implementing the CalcEngine class, I used benchmarks to compare its size and performance with alternate libraries and make sure CalcEngine was doing a good job. A lot of the optimizations that went into the CalcEngine class came from these benchmarks.

I compared CalcEngine with two other similar libraries which seem to be among the best available. Both of these started as CodeProject articles and later moved to CodePlex:

- NCalc: This is a really nice library, small, efficient, and feature-rich. I could not use NCalc in my Silverlight project because it relies on the ANTLR runtime DLL, which cannot be used in Silverlight projects (at least I couldn’t figure out how to do it).

- Flee: Unlike CalcEngine and NCalc, Flee keeps track of formulas, their values, and dependencies. When a formula changes, Flee re-evaluates all cells that depend on it. One of the interesting features of Flee is that it actually compiles formulas into IL. This represents a trade-off since compilation is quite slow, but evaluation is extremely fast. I decided not to use Flee in my Silverlight project because it is relatively large and the parsing times were too long for the type of application I had in mind.

The benchmarking method was similar to the one described by Gary Beene in his 2007 Equation Parsers article. Each engine was tested for parsing and evaluating performance using three expressions. The total time spent was used to calculate a “Meps” (million expressions parsed or evaluated per second) index that represents the engine speed.

The expressions used were the following:

1 2 3 | 4 * (4 * Atan(1 / 5.0) - Atan(1 / 239.0)) + a + b Abs(Sin(Sqrt(a*a + b*b))*255) Abs(Sin(Sqrt(a^2 + b^2))*255) |

Where “a” and “b” are variables set to 2 and 4.

Each engine parsed and evaluated the expressions 500,000 times. The times were added and used to calculate the “Meps” index by dividing the number of repetitions by the time consumed. The results were as follows:

| Time in seconds | Speeds in “Meps” | |||

| Library | Parse | Evaluate | Parse | Evaluate |

| CalcEngine | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.04 | 1.18 |

| NCalc | 7.1 | 5.7 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| Flee | 1,283.0 | 0.5 | 0.00 | 2.91 |

| CalcEngine* | 10.7 | 1.5 | 0.14 | 0.99 |

| NCalc* | 145.2 | 5.7 | 0.01 | 0.27 |

Some comments about the benchmark results:

- CalcEngine performed well, being the fastest parser and the second fastest evaluator (after Flee).

- Flee is literally “off the charts” on both counts, almost 900 times slower parsing and 2.5 times faster evaluating than CalcEngine. Because Flee compiles formulas to IL, I expected slow parsing and fast evaluation, but the magnitude of the difference was surprising.

- Entries marked with asterisks were performed with optimizations off. They are included to demonstrate the impact of the optimization options.

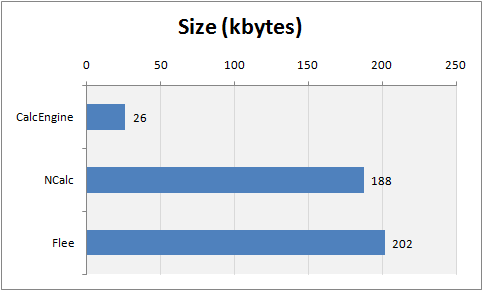

In addition to speed, size is important, especially for Silverlight applications that need to be downloaded to the client machine. Here is a comparison of library sizes:

| Library | Size (kB) |

| CalcEngine | 26 |

| NCalc | 188 |

| Flee | 202 |

CalcEngine is the smallest library by far, more than seven times smaller than NCalc. If necessary, it could be trimmed even further by removing some of the less important built-in functions.

Conclusion

The CalcEngine class is compact, fast, extensible, and multi-platform. I think it is different enough from NCalc and Flee to add value for many types of projects, especially Silverlight applications like the one it was created for. You can see the Silverlight app in action in the image below.

I hope others will find CalcEngine useful and interesting as well.